Frits lives with his parents who he both loves and belittles. His father is deaf, a casualty of child labour, and his mother spends her life in a state of anxious ignorance. His days are occupied by a mundane office job, his evenings by attempts to stave off the lassitude that threatens to consume him. He calls on his friends, gets blind drunk, is casually insulting then chides himself for it, inspects parts of his body minutely, spins stories – some dark, some ridiculous – and sleeps when all else fails, falling into nightmarish dreams. He’s haunted by a terrible fear of conversational gaps, turning frequently to the topic of baldness with which he’s mildly obsessed when one looms on the horizon while nervously checking how many hours are left before he can duck out.

Published just after the war, this is a bleak, darkly funny novel set in a city that has only recently been liberated from five years of Nazi occupation, rarely mentioned by Frits and his pals. Reve’s skill lies in the humour, underpinned with pathos, with which Frits’ chronic restlessness is portrayed. He has you grimacing with recognition as Frits wonders how long he can keep up a listening face for the raconteur incapable of editing his story’s dull details, then cringing at his pomposity until we learn that Frits – once a star pupil – dropped out of school early. Despite his superior attitude, he’s a failure alongside his friends, condemned to be an outsider. There are a few glimmers of self-knowledge: listening to tales of his parents’ generosity during the war Frits is shamed by his resentment of it but he’s soon back to disparaging them. The book ends on New Year’s Eve. Frits’ vain search for friends to share a celebration with after a joyless meal with his parents sets the mood for the following year which looks likely to be not so very different from the one that came before.

I notice that you don’t give much away about your own response to the novel. For myself, I read your review and thought, why would I want to read about this? Then I thought again and realised that this reminded me of a discussion at an IBBY conference some years ago when a group of British and European authors were brought together to debate what I can only call the. ‘boundaries’ of Children’s Literature. It very soon became apparent that what was considered appropriate and interesting material in the UK and what in some European countries which included Holland, was very different. There were some genuine attempts to pin down why there was such a difference and, I’m afraid, from one particular author in the audience, a response which amounted to ‘well they’re foreigners, what can you expect’. The nearest I can come to summing up what the differences we were observing were is that the plot lines were flatter and the outcomes bleaker. Your description of this novel makes it sound similar.

That sounds like an interesting if slightly unsettling debate. In many ways I’d say we’re quite similar to the Dutch although this novel was written very shortly after the war and, of course, their experience was very different from ours. British critics lauded it to the skies when it was published last year but my own response was ambivalent but admiring. It’s a bleak novel, often very funny. Frits’ ennui becomes oppressive but then that’s how it is for him. It won’t be on my books of the year list but it’s well worth reading.

I’ve noticed quite a few positive reviews of this book over the past few months, so I’m glad to see that it comes with your seal of approval too. Ennui is a difficult quality to pull off successfully in a novel without it becoming too mundane or bleak – I’m sure the dark humour really helps here.

Yes, the novel’s dark humour certainly leavens its bleakness. Frits’ – literal- inspection of his own navel is a particularly smart, funny metaphor!

Wow; best novel of all time?! No pressure, no expectations there, eh? Yikes. But it sounds like a worthwhile read for sure. The irony of the book ending on New Year’s strikes hard, I bet.

It most certainly does.

This might be my book for the train to Bath tomorrow. Can’t quite decide yet – nothing too heavy going for a train. But obviously a crucial decision! Terrible when you pick the wrong book and it is the only one you have with you. See you Friday.

Hmm… might be a bit dark for the train. I’d pack two books! See you soon.

I am torn about reading this novel. The fact that it was rated the best Dutch novel of all time has me really curious, but honestly, I don’t really want to read about one man’s boredom. I can’t decide if the humor would make it worth it.

I suspect on balance it wouldn’t if you’re not drawn to the premise although it may be worth reading few more reviews.

I have seen mixed reviews of this novel, which I always think sounds really good, very atmospheric of a time and place. You make it sound very appealing.

I’m not surprised that the reviews are mixed despite its tag as the favourite Dutch novel. Frits is not a very companionable character however he’s certainly a memorable one.

I have mixed feelings about reading this novel but nevertheless your review have convinced me and reall who can refuse Pushkin Press books

Pushkin Press are excellent, aren’t they? Along with Oneworld, they’re fast becoming one of my favourite publishers.

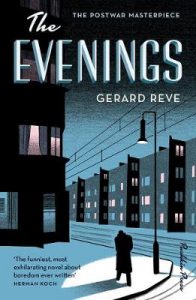

This sounds a rather grim and bleak Christmas novel, is there much of a glimmer of hope within it? Another very arresting cover, however. What did you think of this book in the end? Did it deserve its plaudits?

Definitely not a jolly Christmas book, and I’m afraid there seemed to be no glimmer to me, I’m afraid. As for whether it deserved its reputation: not for me but I’m glad I read it and there’s much to admire.

Sort of shocking that a book about boredom was so popular, mind you, at that time, people were probably starved for a bit of boredom considering what they had just endured for the past decade…

That could well be the case. Frits’ self-absorption is such that that there’s very little mention of the war and occupation.

I had mixed feelings about his book. Its portrait pod a dull and meaningless life was very well done I thought and the character of Frits was certainly memorable. No wonder he had so few friends, I wouldnt have wanted to spend time with him either given how few social skills he has but h n o did feel sorry for him at times. Best Dutch novel? Surely not.

According to the Dutch Society of Authors, although I don’t know how many people were involved in the poll. I thought it caught the oppressiveness of boredom very well but wasn’t sorry to come to the end of it.

I was similarly happy it wasn’t longer.

I do really want to read this, but I think I have to wait for the right mood. If I encounter Frits when I’m feeling short of patience I think I may end up tossing it aside!

Very wise. He is quite exasperating.